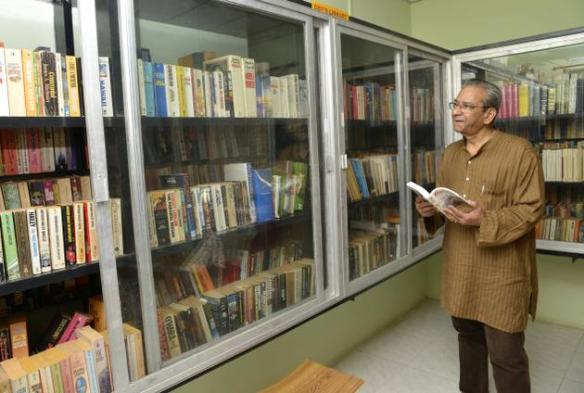

Surrounded by her students. Photo: E. Lakshmi Narayanan THE HINDU

As a student, Aarti C. Rajaratnam didn’t quite walk the conventional path. She hung out more with the watchman than in class, trained the school dog to pee on teachers, wrote 14 plays one year and read her way through the school library. Once, a geography teacher interrupted her while she was buried between books, and asked her to cut out the newspaper’s satellite weather forecast picture for two weeks, paste it sequentially in a notebook and trace the movement of the fuzzy white patch. Then the teacher said, “That’s the trajectory of the South-west monsoon. That’s also what’s on Page 144 of our textbook. Now would you like to come to class?” Aarti did.

In adulthood, she went on to design a curriculum that taught through play and took it to 400 schools across rural Tamil Nadu, incorporating teaching tools made from trash. She also became a clinical psychologist, specialising in child and adolescent mental health, to help children drained by an unfriendly education.

Aarti’s work with children began during her Masters in Delhi University, where she interned at Rajkumari Amrit Kaur Child Guidance Centre assessing and counselling 7,500 children in 14 months. “It’s where I learnt to fight for poor and differently-abled children, find schools that would take them in with their difficulties and actually care for them,” she says. In June 2002, Aarti brought these skills back to her hometown, Salem, and began Kriti Play School in a friend’s spare garage, along with Vasanthi Subramaniam. “We wanted to create a space where all nine domains of a child’s development — sensory, self-help, language, physical and gross motor, fine motor, cognitive, emotional, social and spiritual — could be enhanced through daily graded activities. Every child learns through visual, auditory or kinesthetic aids, so we brought these into the classroom too,” she says.

Aarti’s agrees with philosopher Michel Foucault’s theory that prisons and schools have similar architecture because the aim in both is to discipline and correct. “How can you nurture creativity that way?” she asks. Kriti, therefore, has classes without the standard chair-and-desk in rows but with walls lined with everything from tweezers to kitchen scrubs as teaching aids, and a central empty space for children to use them. Over 12 years, Kriti developed 180,000 different activities, each documented to observe the varied skills it promoted. “All higher-order thinking can be traced down to the most basic physical skill. So crawling and reading are linked, as are writing and climbing, and developing better stereognosis, for instance, can help a child weak in calculating probability. By compartmentalising education, we’re actually restricting learning,” she says.

All through Aarti’s journey of discovery at Kriti, she ran a counselling centre as well and observed increasing numbers of neurologically capable children unable to perform at school. Many of them had learning disabilities. “That’s when I realised just how deep-rooted the problems of our education system were and that I was, thus far, reaching out only to people who could afford it. There were thousands in the villages who couldn’t,” she says.

Thus began Aarti’s collaboration with People’s Solidarity Association (PSA), Trichy, which had a network of micro-credit women’s groups across villages in Tamil Nadu. Together, they began one-roomed supplementary education centres where rural children spent their evenings strengthening their English and Math skills through the activity-based curriculum. “The idea was to use community resources to sustain these centres,” says Aarti. So a centre with 20 children, for instance, would have one teacher who was a member of the micro-credit group or an unemployed youth who’d finished school. “We don’t need B.Ed. graduates. We find just one person who wants to give back to their village and train them in the curriculum,” says Aarti.

The training focuses on using locally available material as teaching tools. Hence empty coconut shells, discarded tyres, kola maavu, soda bottle caps, painted stones, feathers, ropes, wires and leaves find their way into daily learning. Explains Aarti, “The training itself teaches through activities, so the trainee gains insight from experiential learning and is able to create teaching tools from absolutely anything.” Aarti also has an elaborate waste management and recycling system in place in which trash from urban schools is directed to the rural centres and converted into education aids there. For example, an activity like threading beads through a rope for hand dexterity is replicated in the village using empty sketch pen barrels instead of beads; and wooden tools are recreated from the cardboard sides of used notebooks. Aarti works closely with each centre for the first three years, after which they grow into self-sufficiency. Over 13 years, through tie-ups with various organisations, today, there are 400 such centres across rural Tamil Nadu.

“A centre survives only if the villager has a sense of ownership over it,” says Aarti. So, in one village, the children’s fathers built the resource room and the centre provides a daily meal made from egg, milk, rice and other produce sold by the micro-credit group mothers. Some centres even kick off with training on pre-natal health, child care and nutrition for mothers. Every centre, though, compulsorily runs through a module on child sexual abuse that teaches the children about their physical, emotional and sexual safety. “There’s much that goes unnoticed because it’s not spoken about and, most often, it is incest. To begin healing, the child needs a therapeutic ally and we train teachers to be that,” says Aarti.

Every new village has caused Aarti to combine her training as a psychologist and experience as an educationist differently; first to gauge the needs specific to the area and second to formulate aid from available resources. The two were tested most vehemently, in early 2005, when People’s Watch roped her in to counsel child victims of the tsunami. Over 7,000 children in 11 villages such as Colachel, Muttam, Kelamanakudi and Mellamanakudi had lost their families, homes and schools. “We couldn’t even think of restarting education because the children had to overcome trauma first. They also had to learn to forgive the sea, which was once their home but had turned hostile,” she says.

The process began by training two teachers — each from the different schools in the villages — to become barefoot counsellors equipped with basic group therapy skills using a combination of creative methods such as puppetry, drama, music and art. Over six months, children sketched their thoughts on blank paper and the counsellors identified those with post-traumatic stress disorder from their art. The early drawings show calm waters full of floating bodies, villagers running from rising waves, families drowning, fishing boats hoisting the dead, mass graves, destroyed churches and schools, suicide and abandonment. Over time though, the pictures evolve to depict rebuilt homes and schools, small festivities, sowing and reaping — semblances of normalcy returning.

Close to a decade has passed but the challenges faced on the coast have permanently shaped Aarti’s approach to teaching, as have the experiences of easing first-generation learners from villages into education. Despite so much accomplished, Aarti interrupts every few lines of conversation with, “We’re here on this earth for barely a few years, but there’s so much we can do that time!” Even so, her immediate plans for the future remain unwritten. She says, “I know there’s a purpose for me and that plan will unfold in time; I’m just an instrument here.”

Published in The Sunday Magazine on April 18, 2013

http://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/teaching-without-books/article4609709.ece

Story behind the story

In the four hours that Aarti and I spent together, I can’t pick which of her lines moved me most. Our conversation came at a time when much internal questioning had been on, as has been for a while now. And time and again I’ve found that the people currently in my life inadvertently answer these quiet questions. Aarti was one of those. “When you come into the knowledge of your purpose, the way for its fulfillment is ready for you to find it,” she said. It’s what sent her for six months to the tsunami coast without a bank balance to match. Strength of conviction is what its called. The fulfillment of that purpose, she found, brings with it a profound sense of being truly alive, the experience of every moment in all its fullness. I’ve been listening to stories of people who’ve found that pure and absolute freedom, some of it in unimaginable ways. Incidentally, it was in one of these stories of pure insanity, that I found one of the most accessible definitions of this freedom: it’s to be able to fulfill unwritten dreams but take people with you on that journey. It’s reassuring to know the answer doesn’t lie in the unaccompanied climb.